L'immensità review: dual portraits of outsiderhood in 1970s Rome

A tale of an unhappy family tinged with hope. Also - men are trash!

SPOILERS BELOW!

+ content warning: transphobia, domestic abuse, Celeste’s misandrist rage

Having seen the trailer a few times on my many jaunts to the cinema, I went into L'immensità expecting the story to revolve around the gender dysphoria and a trans teenager coming of age. However, this storyline is just one aspect of what turned out to be a more intertwined tale of a family in quiet crisis.

So first, a summary: a family of five in 1970s Rome, gorgeously portrayed in all its brown and orange glory. Clara, Spanish born mother, is glamorous, beautiful, and playful. She takes great care to shower her 3 children - little Diana, rule following Gino, and preteen Andrea. Andrea is the Italian form of the English Andrew, and he is almost always referred to as Adri (short for Adriana), his birth name, by almost everyone). I will be calling him Andrea and referring to him as male, as most reviews I have read have also done.

Clara’s husband Felice is a controlling patriarch, claiming his entitlement as head of the family whilst failing to show more than the bare minimum of love for his children. The children exist for his approval, and he makes it clear that it is Clara who is in charge of raising them, criticising her instead of assisting her when he feels she is not doing a good enough job. He simply created his offspring and wishes them to be obedient and subservient to him. Felice has many affairs which are an open secret, and true to stereotypes, manages to knock up his secretary. When Clara asks to separate, Felice taunts her; where will she go, how will she survive? How will this beautiful, creative, resourceful, loving, and kind woman survive without her man who regularly rapes and beats her? How could she possibly exist without a weak, cowardly, cruel domestic dictator bringing her down? God only knows.

Despite this difficult parental dynamic of love and rage, the children (played by amateurs) are close and, for the younger two at least, seem to still exist in the playful and innocent paradigm of childhood. Andrea, the eldest, has not left this innocence entirely, but he has certainly been exposed to the difficult issues of growing up enough to be deeply pessimistic. Some reviews I have read criticise Andrea for being scowling and unlikeable. To them I beg you: do you not remember being 13 years old, for the love of god. In the strictly gendered Catholic world of 1970s Italy, cutting one’s hair short, wearing baggy clothes, and asking to be called by a boy’s name leaves Andrea constantly ridiculed and his wishes to be seen for who he is ignored. It would have been ridiculous to portray him as anything but miserable. This is even before we go into how he witnesses his mother’s suffering.

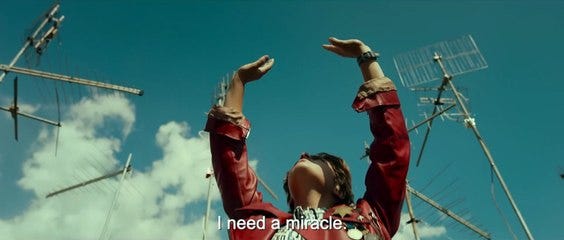

In the opening scene of the film, Andrea makes a pentagram out of string on the roof of his building, and begs for a sign. Later, he steals communion wafers from church and asks god for a miracle. Andrea is looking for answers everywhere, knowing that they do not exist on the same mortal plain where he exists. Across from his apartment building, beyond a field of reeds, there is a traveller encampment on a disused construction site. He has been told repeatedly not to go through the reeds, but does so out of curiosity. There he meets Sara, a girl of his age, who is the only character in the film to call him Andrea. Sara is the relief in his life. They straddle the line between child and teen. They run around a play like children, but also try cigarettes together and exchange an awkward teenage kiss.

Felice’s secretary comes to visit Clara at home, and it is unsaid yet clear that she has become pregnant with Felice’s child. When Clara angrily confronts her husband later on, he responds with astonishing violence. It is not explicitly shown, but difficult to watch, even though it lasts no longer than ten seconds. A brutal and domineering man holding his wife down on the ground and he punches her for daring to be angry that his affairs will soon lead to new life.

Eventually, Clara accepts that she is on the verge of a nervous breakdown and goes to stay in what she describes as a nice villa in the country. We later discover that she has been sent to an inpatient mental hospital to recover from her affliction of, erm, her husband beating her to a pulp whenever she opens her mouth. Clara’s reactions and deteriorating mental health are not a deep seated psychiatric issue, and her depression is not a pathology. She is reacting, rather understandably, to the difficult circumstances of her life. At no point are the causes of her troubles addressed. At no point does anyone consider than she should be allowed to separate from her violent husband, and be with her children whom she loves so deeply. At no point does anyone see that none of what troubles her come from within. It is a terribly sad portrait of how women who did not behave as men wanted them to were shipped off the the country and no doubt pumped full of barbiturates to keep them quiet and passive.

In a way, this film has two main characters: Andrea and Clara. I was hoping to see more of a development arc with Andrea, which is what the trailer hints at. Their characteristics play off each other, with the tomboyish Andrea and glamorous Clara complimenting each other marvellously. Even though Andrea has rejected femininity, he has a clear understanding of the misogynistic world he is in. He witnesses his mother being sexually harassed by men on the street, and raped by his father. On both of these occasions, his response is intense, almost uncontrollable anger. It is immensely brave of him, not only to challenge a group of adult men in the street about their behaviour, but to scream at his father to leave his mother alone, when he knows full well what this dreadful man is capable of.

I went into this film thinking it was about Andrea, but Clara is really at the centre of this story. I’m no authority on motherhood, having been raised mostly without mine and having no interest in being one myself. But you would have to be some sort of stone cold psychopath to not see Clara as a marvellously kind and loving mother. She is patient with her children, and lets them be young and enjoy their limited days of innocence. She is playful and is far more trusting of the children around her than the adults. Sure, she doesn’t quite get what Andrea is going through, but her attitudes towards her child’s tomboyish turn are extremely accepting given the context.

And her reward for this kindness, this patience, this open mindedness? Violence, accusations of failing to raise her children properly, and eventual institutionalisation. That was the saddest part of this film for me. Not only because being sent away to be drugged into submission is awful, but because that’s how women who didn’t behave as they were expected to were treated back then.

Perhaps it hit me extra hard as a stubborn and argumentative woman with a laundry list of mental health diagnoses that I’ve collected like pokemon cards over the years. I would have absolutely been banished to somewhere like that in a heartbeat. This trend of throwing people in spicy brain prison is explored in my last newsletter, where I discuss gay conversion therapy for teenagers in But I’m A Cheerleader and Euphoria. It’s all for the same purpose - conform or be beaten into doing so. As I said last week, praying the gay away is something we laugh at now, without giving much thought to the fact that the gay teens we apparently now accept have had their undesirable shoes filled by trans teens, the new enemies. It’s all happened in a rather short space of time - which is obviously a good things, and it’s further proof that societal attitudes can change for the better in less than a generation. It also helps mask how recent these bigoted attitudes were, made extra easy when new pariahs conveniently appear to fill the vacuum of bigotry and hatred.

We have made great leaps forward in how we treat women like Clara… right? Since 1969 in England a couple could divorce if they could argue that the marriage had broken down irreparably. Which is fine, unless your violent pig of a husband refuses to comply. No-fault divorces were only enshrined in law in 2020 and came into effect LAST YEAR. Marital rape has only been a crime since 1992, the year before I was born; before then, a woman gave up her right to give consent when she walked down the aisle.

So it’s a “better late than never” scenario with the legal routes to leaving your husband. Though we no longer send women to country retreats to recover from being victims of domestic abuse, maybe we should. Now, abused women are forced to stay at home, to be beaten to a pulp by their husbands there instead. This was particularly dreadful during the pandemic, when you couldn’t “just leave”. We’re poorer than ever and house prices continue to balloon, so good luck buying a new house to be safe in. Want to rent? Landlords can just refuse you and your family because you have children with you, and evict you if you’re too much of a nuisance. So, to a refuge? Budget cuts mean that women’s crisis centres and refuges are having to turn vulnerable women away, back into the arms of their abusers, according to Women’s Aid and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

One of the more frustrating aspects of this is, surprise surprise, the “trans debate,” where horrible cunts like J.K. Rowling and her terf army spew transphobic rhetoric which denies trans women to access rape crisis centres and accuses trans women of preying on cis women in these centres. Like they have nothing better to do. Let’s all remember who the common enemy is - it’s men beating up cis women, and it’s men also beating up trans women, and it’s men beating up children. It’s men beating people who aren’t men up, period.

So why have I gone off on this miserable fucking tangent in my nice film review? Because it’s easy to walk away from these films which portray violent misogyny and think “thank god we’ve moved on from all that.” But we haven’t. Women’s liberation and rights is something that has always been framed as something women need to fight for and be granted, rather than as men denying us the right to exist as equals to them. It’s women who are told to leave their violent husbands, and never men being told that they have no right to beat their partners. Every women knows another woman who has been raped or assaulted, but men always claim that all their friends are super nice guys who would never. Someone is lying, and it’s not us.

So the moral of the story? Women, keep yelling, keep dancing, keep questioning, keep challenging, and keep being god’s most beautiful perfect creatures. Keep women like Clara in mind next time to hear someone calling a woman crazy. And fellas - it’s up to you to stop domestic violence and abuse, not us. Call out your friends, challenge bad behaviour, and reinforce treating women like actual human beings, every fucking day please. Yeah yeah yeah, we’ve come a long way, but I will not shut up until the universe is a matriarchy and every man who has ever laid a finger on a woman rots away in prison for eternity.

L’Immensita is streaming… nowhere. And no screenings either! Boooooo. Naughty streaming instructions can be found here.

celeste for president xxx