Readers of this blog may not be aware that before I studied all things Eastern European whilst working in the music industry here in Amsterdam, I spent 4 years working as a track cycling coach at the ORIGINAL London Olympic Velodrome in Herne Hill (not that pretender at Lee Valley). But that’s a fun story for another time.

For now, I need to talk about that Olympic men’s Madison race.

Having spent years trying to reinvent myself as a cool and interesting person, my Instagram chums have been treated to learning about Madison racing against their will, and I have quite spectacularly outed myself as being really into an obscure sport.

Unfortunately, my dear readers, you won’t be spared from this pain either.

Here’s the basics:

The Madison is an endurance bunch race where teams of 2 take turns. At the Olympics, the women’s race is 30km (120 laps of the velodrome) and the men’s is 50km (200 laps). In this field there were 15 teams of 2 riders, so 30 riders in total.

There are sprints every ten laps, with 5, 3, 2, and 1 point available for the first 4 riders over the line. You can get 20 points if you lap the field (overtake the slowest group of riders) and lose 20 points if the field laps you.

There’s one “racing” rider, who maintains the team’s top speed, and one “resting” rider, who takes a breather. They tag each other in and out using a handsling which allows the racing rider to transfer their speed over to the resting rider. Just watch the gif:

Still confused? I don’t blame you. Here’s a 1 minute explainer from the UCI.

The women’s race took place on Friday without much incident - a dodgy change by the Swiss team had them on the floor for a minute but other than that, smooth sailing.

Italy gold, GB silver, Netherlands bronze, with the Brits being the only riders on the podium who hadn’t lapped the field to get 20 points. It’s a great example of how there are so many ways to do well at bike racing - be bold and brave, or stick to a schedule?

The reason I’m only doing an in-depth dive into the men’s race and not the women’s is because the women’s race was pretty normal. The same cannot be said for the men’s.

OK let’s get cracking.

Housekeeping!!

There were a lot of big names in this field, and the fact that I’d heard of a lot of them despite not really watching much bike racing in the last 7 years means these guys are hardened pros. The race included:

Denmark’s Michael Mørkøv (39), defending Madison gold medallist from Tokyo, seasoned Six Day racer, 3 time Madison World Champion (2009, 2020, and 2021 - how’s that for range). I could not for the life of me tell you how to pronounce his last name.

Spain’s Albert Torres (34), 2014 Madison World Champion and 5 time European Champion in the Madison and omnium. He was paired up with Sebastian Mora (36), who has 1 World and 6 European titles.

The Netherlands’ Yoeri Havik (33), two time World Champion in the omnium and Madison, and winner of 6 Euopean Six Day titles between 2011 and 2020. Him and his partner Jan Willem van Schip (29) are the reigning Madison world champions.

Germany’s Roger Kluge (38), 2 time Madison World Champion and 4 time World Champion in the Madison and omnium, plus a silver in the Points Race way back at Beijing 2008. He was paired with Theo Reinhardt (33), 2 time World and 3 time European Champion in the Madison.

Italy’s Elia Viviani (35), Omnium gold medallist in Rio, points classification winner of the Giro D’Italia, 2 time World Champion in the omnium and more European titles than I can be bothered to mention. His partner Simone Consonni (29) is champion in the Team Pursuit at World and Olympic level, and his baby sister Chiara won the women’s Madison just the day before.

If this is all Greek to you, it means this race was chock full of Madison champions, Six Day Legends (which is a ton of Madison racing), and experts in similar track endurance disciplines. They could do this in their sleep.

The Race

Remember, it’s 200 laps.

About 5 seconds after the starting gun went off, the Austrian pair of Kokas and Schmidbauer immediately ride off the front to attempt to take a lap.

I’ve not really been following track cycling since I left coaching in 2017, but I have never heard of either of these riders. Schmidbauer (22) rides for an Austrian UCI Continental team (the second highest tier in professional cycling), and Kokas (19) rides for an Austrian team that Pro Cycling Stats describes as a “club”. The pair are Under 23 European Madison champions.

Now, cycling isn’t one of those sports where being young is an advantage; many of the field in the Madison are firmly over 30, and it’s a race where years of experience can do a lot of good (please refer back to my list). Furthermore, Anna Kiesenhofer’s surprise road race win in Tokyo was Austria’s first cycling medal since the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. Sure, Adolf Schmal’s gold medal 128 years ago was for track cycling, but this was only because bicycle gears had not yet been invented. Put simply, Austria aren’t one of the big cycling nations. No shade to Kokas and Schmidbauer, but I’m sure they’d also agree that they weren’t medal favourites going into this race.

So what does this early attempt to take a lap mean? At 199 laps to go, the riders are bunching up and preparing for their first sprint in 8 laps time. It’s not a super fast pace yet.

Riding off the front like this gained Austria 25 points: 20 for lapping the field, and 5 for crossing the line first at lap 190, shortly before they joined the back of the bunch.1 I imagine that Austria used this tactic in the (most likely correct) belief that this was their only chance to pick up some points and place respectably, given the conditions outlined above. These two youngsters would struggle to pick up sprint points in such an experienced field.

But it came at a price. The Austrian pair used up all their energy taking that lap, and went from being in first place with 25 points, to *checks notes* -55 points. They got lapped by the field four times - losing 20 points each time - until the commissaires (cycling referees) pulled them out of the race.2

Before they exited the race, however, the big boys of the bunch started picking up points at the sprints every ten laps. In the duration of the race, Italy, Japan, Denmark, Portugal, and Czechia all managed to lap the field and get 20 points apiece. The Netherlands and New Zealand both tried to take laps and didn’t manage it, and to everyone’s great surprise France lost a lap (I imagine Benjamin Thomas is pretty tired right now). Judging by Australia’s last place with -49 points, I imagine they must have been lapped at least three times as well.

At the start of this Madison, 12 of the 30 riders had already completed the omnium, which combines 4 endurance races in one day.

With these riders, some of them already exhausted, launching attack after attack to either take laps or win sprints, this climactic event leads me to my next major talking point:

Crashes

Falling off your bike every now and then is an inevitability in cycling, but that doesn’t mean you want to get caught up in a crash. The velodrome is a big pringle crossed with a centrifuge, where riders who crash can hope, in the best case scenario, to skid along the boards, rip their shorts and lose a bit of skin.

The first crash was fairly inconsequential, if not totally stupid. Germany and New Zealand got tangled up doing a change and two riders hit the deck. Everyone was fine at they got back up and rejoined the race, no points or limbs lost. Not a huge problem.

The main 3 crashes of the race happened within the last 40 laps.

Crash 1

The first of these was a strange altercation that has GB cycling Twitter screaming aggravated assault because British people really have nothing better to do right now. With 40 laps left to go, Dutch rider Jan-Willem van Schip barged past British rider Ollie Wood on the banking, which Alex and I have pored over in slow-mo over breakfast. It was definitely van Schip’s fault, and at first I thought it wasn’t intentional… but come on, what other reason does such an experienced rider have in such a high profile event. At this point, the Netherlands - who are reigning World Champions in this event - sat in a very unimpressive 11th place, and were probably realising that time was running out to score points and take laps. They chose recklessness over tactics to solve this, which was stupid and impulsive.3

The effects of the crash led to the British duo of Woods and Stewart losing a lap. At the time, the comms didn’t think much of it, probably because of all the other stuff they had to keep an eye on. What I know now, however, is that The Netherlands’ result of 7th place was relegated to disqualification late on Saturday, with a well-deserved fine of 1000CHF for van Schip.

With the end so near, the race was fast, people were getting tired, there were fewer points to be won and the final standings of the race were beginning to look more and more certain. Remember, this is the showstopping event of the track cycling programme. Everyone wants that gold, especially those riders who may not get picked for LA 2028. Madison and points races are an exercise in quick maths as well as in riding your bike, as winning the race can be done with smart calculations and knowing when to go for it and when to let it go.

Crash 2

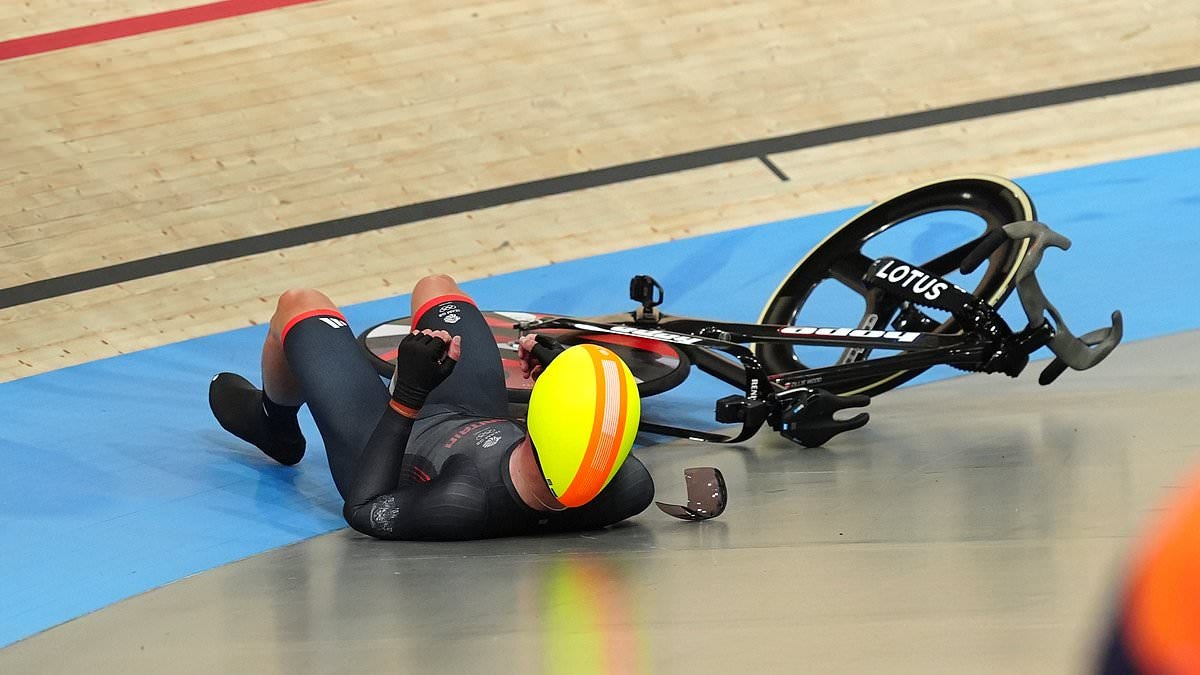

Between sprints 17 and 18 - 30 and 20 laps to go - things began to get really hairy. There was no real bunch left as riders formed smaller chasing groups to attack and counter attack. At 28 laps to go, a touch of wheels between a New Zealand rider and Belgium’s Lindsay de Vylder sent the latter careering down the banking. Spain’s Albert Torres, who was in 6th place at this point, had absolutely nowhere to go, and went flying over the handlebars as his bike unclipped and bounced off into the distance. It’s a miracle that nobody else got hurt.

It’s hard to see in the grainy gif but Torres landed hard and broke his helmet in the process. The adrenaline was clearly pumping because he spent the rest of the race on the safety zone4 arguing with the commissaire who told him there was no way he was rejoining the race after hitting his head. Torres was desperate to rejoin - this might be his last Olympics - and the Spanish team doctor was on his side arguing that look, he’s fine. But the commissaire was right: it would have been irresponsible to let him get back on and it sets a dangerous precent in a sport already fraught with danger. It turned out that Torres fractured his hand in the crash, so it was for the best that he didn’t rejoin the holding hands race.

Cyclists are insane - throughout the road season you see riders dip below the barriers at level crossings and hoof it over the rails because a high speed train is about to interrupt the race. The stories of toughness on the bike are stuff of legend. Geraint Thomas finished the 2013 Tour De France after fracturing his pelvis on the first stage (of twenty one!). Tyler Hamilton fractured his collarbone, again on the first stage, of the 2003 Tour de France and finished in fourth place, having ground his teeth down to the root from the pain.5 When I broke my collarbone in 2013 the texts poured in from my bike friends offering their congratulations, and that I was a real cyclist now. Pushing through the pain and persevering even though your body is screaming at you to stop is characteristic of all athletes who perform at a high level; cycling is unique in that the pain is caused by hitting the ground at 40 miles an hour rather than the usual lactic acid overload or an unfortunate ACL tear.

So yes, it comes as no surprise that Torres was desperate to get back on and finish the race. Perhaps a medal wasn’t possible, but a respectable placing was. In the end, his partner Mora rode on alone, losing a lap along the way with their final score of -4, in 8th place. Even if an independent medical check had been possible, with 30 laps to go there’s no way he could have been cleared in time. The crash also disrupted Belgium’s ambitions; you can tell de Vylder hit the ground hard as he gingerly gets back on his bike to continue the race, where Belgium finished 10th after losing a lap. They were probably in contention for the medals. Fabio van den Bossche won a bronze in the omnium, and Belgium has a rich pedigree in excellent Madison riders (my absolute favourite of which, Kenny de Ketele, now the Belgian coach, was sat in the stands looking pretty stressed out).6

We’re now only a couple of sprints from the end, and the teams with potential to medal have thinned. Canada and Austria have been pulled out of the race; France and Australia are having a terrible, terrible day; Spain, Belgium, and Great Britain are bruised and sore; and the Netherlands would end up being disqualified anyway. Czechia and Japan managed to take a lap each, putting them in contention for medals. Italy have been in gold medal position for most of the race. Denmark look as cool as cucumbers and are staying out of trouble. New Zealand are riding phenomenally. Germany are in there somewhere, and so are Portugal, though neither pair appear to be serious contenders. Seven pairs are left fighting it out, and it’s close.

Crash 3

With the worst timing imaginable, Italy - who are in gold medal position and have been for the last 100 laps - fluff a change, and Consonni hits the ground. They miss a sprint and a chance to win points, and Consonni has to balance out the pain of the crash and the adrenaline of the race as he jumps back on looking like a man on a mission. There are only 2 sprints, with a maximum of 15 points, to be won by the time the Italians are back on the track.

The Closing Laps

At 21 laps to go, there are 5, 3, 2, and 1 points to be won at the 18th and 19th sprints, and then 10, 6, 4, and 2 at the final sprint. The pace is blisteringly high and riders are probably a little jumpy after 3 crashes in quick succession. Trying to gain a lap now would be crazy… but Portugal somehow managed it, catapulting them into the silver medal position after having been nowhere significant all race. No one saw this coming and no one was prepared to deal with it.

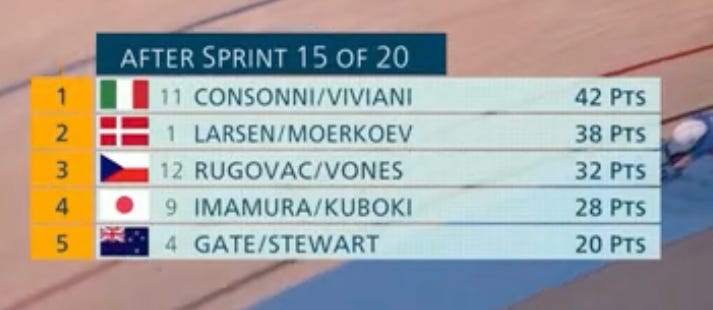

The chasing group of 5 riders - Italy, Germany, Portugal, New Zealand, and Denmark - were at the front, and Italy were struggling to hold on. The crash dented their dominance. Let’s take a moment to look at the standings in the last half of the race - except after sprint 13, which the BBC broadcast chose not to share with us. Maybe they’re superstitious.

What do these stats tell us?

At sprint 18, Portugal were sat comfortably in no man’s land in the standings with 20 points in 17 sprints. Gaining a lap - 25 points in total - put them in gold medal position with nine laps to go. No one could have seen this coming, not only because gaining a lap late into the race is quite a feat, but because Portugal aren’t really a track cycling nation.7 Until 3 days earlier their only Olympic cycling medal had been a bronze in the road race in Athens in 2004. 3 days before the Madison, Leitao won a silver in the omnium (an event in which he is the reigning World champion). You wait 20 years for a track medal…

Italy had dominated for most of the race and managed to hold the reigning Danish champions off, and you can see from the standings that they didn’t really gain that many points at all in the second half of the race. Sprint lap points were busy being hoovered up by teams taking laps (with varying success), and teams lower in the standings who were desperately trying to catch up. They were saving their energy for the end, when they’d really need it. Italy knew that they didn’t need to battle for those top points at the sprints because their position was already so good. Italy only gained 5 points in the space of 90 laps; Denmark gained 9.

Consonni and Viviani barely had time to recover from their unfortunate crash when they realised that their dominance throughout the race was suddenly in serious danger. In the blink of an eye, they needed to mark Denmark AND Portugal in the frantic closing laps of the race. Leitao and Oliveira’s status as “pretty good but not likely to win” worked massively in their favour. Race favourites, like Italy and Denmark, would have studied the tactics and riding style of their rivals, learning how to race with them. Not in a “sending spies in with camcorders” way, but just by racing against them over and over again over the years.

As Italy chewed their stems trying to keep up with the bunch, they watched the gold medal - which had looked so certain for so long - slip out of their fingers as Portugal crossed the line, picking up those last ten points and a gold medal for Iuri Leitao and Rui Oliveira, resulting in this magnificent Renaissance-esque photograph.

While Viviani was in tears and the Danes looked extremely grumpy, the Portuguese pair were busy looking completely dumbfounded by what they’d achieved and engaging in what could only be described as froclicking around and hugging each other.

The more cynical among us may argue that their win was only made possible by Italy’s late stage crash, Belgium and Spain losing a lap each because of their crash, Great Britain racing with their backup rider and France just having a bad day. But that’s cycling, baby. It’s a cruel sport in that it cannot be done in lab conditions, and the actions of others can lead to you falling behind. The staggering amount of variables that have to be considered make for such an exciting spectacle. Portugal didn’t win because the conditions allowed them to. They stayed out of trouble, saved their energy, got their points for lapping the field, then saw a literal golden opportunity to make history. So much of shock bike racing results are a matter of “let’s just fucking go for it”.

I hope you enjoyed watching this race as much as I did, and if you’ve somehow made it to the end of this almost 4000 word novella without having watched it, it’ll still be showing on whichever public broadcast you’ve got in your country. Highlights can be found on YouTube here and those mad last 20 laps here. For those watching in the UK or in possession of a VPN, the first bit is on iPlayer here (03:35:00 in) and the rest here.

Interested in giving track cycling a go? Get yourself down to my old office Herne Hill Velodrome in London for a taster session on a track that’s a lot more user friendly than the one you saw on the telly.

Want to watch more racing? The 2024 World Championships are on this October in Copenhagen and the Champions League starts in November at the same track used in the Olympics at Saint-Quentine-en-Yvelines. There are probably loads of local races happening in your area too.

For those new to track cycling, you cease being the “front” of the race once you’ve rejoined the main group.

This may sound harsh, but it’s for the safety of everyone else. If two riders are significantly slower and more fatigued than everyone else, they risk unintentionally getting in the way of the other riders or making riding errors due to being totally pooped. Austria weren’t the only team who DNF’d - Canada’s pair were also pulled out, as they had been in the women’s race the day before. Sounds like there’s something going around the Canadian cycling dorm.

The more conspiratorial among us may see this as revenge for the previous night’s antics. In the men’s bronze medal sprint, GB’s Jack Carlin gave the Netherlands’ Jeffrey Hoogland a right good biffing (at a very slow speed), and despite the Netherlands’ best efforts to have Carlin disqualified, the British rider went on to beat him and win the bronze. Crucially, I think, Carlin immediately realised his error in the sprint and put his hand up in a show of “oops, my bad”. In the ensuing 5 minutes of the comms considering and eventually rejecting a complaint from the Dutch, Carlin was circling the safety zone going “fuck fuck fuck fuck fuck” with gritted teeth.

the inner edge of the track. want to hear more? read The Secret Race, it’s awesome.

he was also Lance Armstrong’s bestie and therefore pumped to the gills with EPO

For those wondering why de Vylder was allowed back in the race when Torres wasn’t - Vylder did not hit his head when he crashed. Being bashed up body wise doesn’t affect your cognition, for better or worse.

Leitao’s biggest result until last Saturday had been as omnium World Champion in 2023, but before that both riders had placed respectably at European level. Confusingly, Rui Oliveira usually rides Madison with his identical twin brother, Ivo.

I have never heard of this sport but I read this as fast as they cycle

Loved it